Craft Beer Qualifier

Is This Brewery Craft?

Check if a brewery meets the Brewers Association criteria for craft beer

Qualification Results

* The Brewers Association requires breweries to be small, independent, and traditional to qualify as craft

When you pick up a six-pack labeled "craft beer," what are you actually buying? Is it the small batch, hand-poured brew from the corner pub? Or is it a beer made by a giant corporation that bought a tiny brewery five years ago and still calls it "craft"? The answer isn’t as simple as the label suggests.

The Official Definition: Small, Independent, Traditional

The most widely accepted definition of craft beer comes from the Brewers Association, a U.S.-based trade group founded in 2005. According to their 2014 guidelines, a craft brewery must meet three strict criteria: small, independent, and traditional.

"Small" means producing 6 million barrels or less per year. That’s about 180 million liters - a huge amount, but still only around 3% of total U.S. beer production. To put that in perspective, Anheuser-Busch InBev alone makes over 100 million barrels annually. So even the biggest craft brewers are dwarfed by the giants.

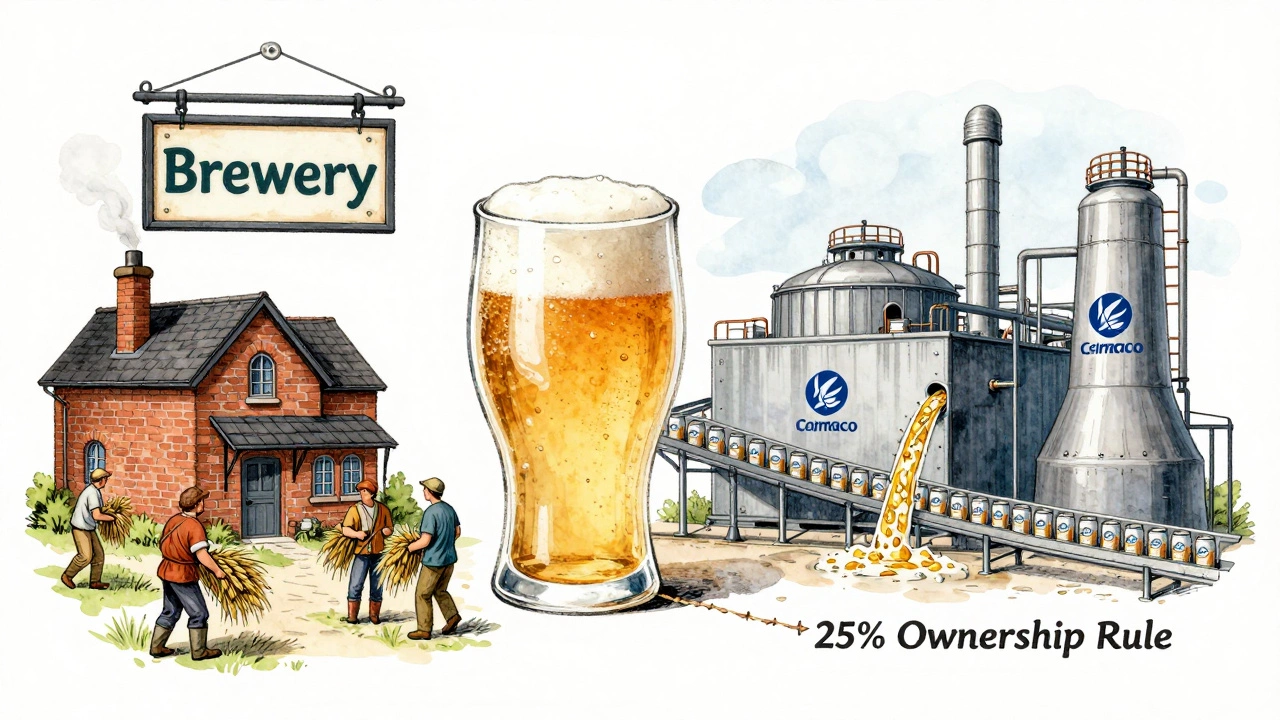

"Independent" means that less than 25% of the brewery is owned or controlled by a non-craft beverage company. That’s the rule that lets a brewery like Lagunitas stay "craft" even after selling 80% of its business to Heineken in 2015. The remaining 75% stays in craft hands, so it qualifies. But it’s a gray area that many drinkers find confusing - and frustrating.

"Traditional" means that at least half of the brewery’s output comes from beer made with traditional or innovative ingredients. The big change here came in 2014, when the Brewers Association removed the old ban on using adjuncts like rice or corn. Before that, breweries using these fillers couldn’t call themselves craft - even if they made complex, flavorful beers. Now, if a brewery uses rice to balance flavor rather than cut cost, it’s allowed. That’s why Yuengling, a 195-year-old American brewery, qualifies as craft today.

Why the Definition Changed - And Why It Still Sparks Debate

The 2014 update wasn’t just bureaucratic tinkering. It was a response to real brewing innovation. Brewers were experimenting. Some used oats for creaminess, wheat for haze, or even coffee and fruit in their recipes. The old rule - that adjuncts "lightened" flavor - was subjective and outdated. Gary Fish, owner of Deschutes Brewery and then-chair of the Brewers Association, put it simply: "Craft brewers should be free to experiment without being penalized by arbitrary definitions."

But not everyone agreed. Beer historian Maureen Ogle called the definition "marketing-driven rather than quality-focused." She pointed out that it tells you nothing about how good the beer tastes - only who owns the company. And that’s where the real tension lies.

On Reddit and beer forums, drinkers regularly ask: "If a beer tastes amazing and supports local jobs, does it matter if Heineken owns 20%?" Some say yes. Others say no. A 2022 survey by the Beer Marketing Research Group found that 68% of U.S. beer drinkers couldn’t explain the official definition. Most assumed "craft" meant "high quality" or "locally made." The truth? It’s about ownership and scale - not flavor.

How Other Countries Define Craft Beer

The U.S. definition isn’t the global standard. In fact, it’s one of the loosest.

In Europe, BrewDog proposed a stricter model back in 2013: no more than 20% ownership by big beer companies, and a production cap of 500,000 hectoliters (about 426,000 barrels). That’s less than one-tenth the U.S. limit. The UK’s Society of Independent Brewers (SIBA) doesn’t set hard numbers but requires breweries to be "relatively small, independent, and brewing quality beer" to use their logo. In practice, that often means under 200,000 hectoliters per year.

Some European craft brewers still refuse to use rice, corn, or other adjuncts entirely - seeing them as cheap shortcuts. In the U.S., those same ingredients are fine if they’re used thoughtfully. That’s why a Belgian-style witbier with coriander and orange peel counts as craft, but a light lager made with corn might still be considered macro - even if it’s brewed by the same company.

The Rise of "Pseudo-Craft" and Corporate Buyouts

Big beer companies didn’t wait around to be outmaneuvered. They started buying up craft breweries.

AB InBev owns Goose Island, 10 Barrel, and Lagunitas. Molson Coors owns Blue Moon and Coors’ "craft" line, including Redbridge and Leinenkugel. These aren’t mom-and-pop shops anymore. They’re divisions with marketing teams, national distribution, and corporate budgets.

And yet - they still carry the "craft" label. That’s because they meet the 25% ownership rule. The Brewers Association doesn’t require disclosure of ownership on packaging, so consumers often have no idea.

In 2017, over 1,200 U.S. craft breweries signed the "Craft Beer Collaboration Pledge," promising to be transparent about ownership. But it’s voluntary. Most don’t label their products with "owned by Heineken" - even though they legally can.

What Craft Beer Really Means to Drinkers

For most people, craft beer isn’t a legal term - it’s a feeling.

It’s the local brewery down the street that uses barley from the next county. It’s the brewer who tweaks a recipe every week. It’s the can with a hand-drawn label and a story behind it. It’s the tasting room where you chat with the owner while they pour you a sample.

That’s why, in a 2023 Hop Culture survey, 61% of craft beer drinkers said "local ownership" mattered more to them than production volume. They don’t care if the brewery makes 5 million barrels - they care if the person who made their IPA lives in the same town.

And that’s the real divide: the official definition vs. the emotional one.

What You Can Look For - Beyond the Label

So how do you know if you’re drinking something that feels like craft beer - even if the label doesn’t say it?

- Check the brewery’s website. Look for info on ownership, sourcing, and production scale. If they’re proud of being independent, they’ll say so.

- Look for transparency. Do they list ingredients? Do they mention their malt supplier or hop farm? Craft brewers often brag about their sources.

- Ask at the taproom. If you can talk to the brewer or owner, you’re likely in a real craft space. Corporate brands rarely let customers meet the people behind the beer.

- Notice the packaging. Handwritten labels, small print runs, and unique designs often signal a smaller operation.

- Check local beer guides. Apps like Untappd or RateBeer show user reviews and brewery details - including ownership.

Remember: a beer can be delicious and still not be "craft" by the official definition. And a beer labeled "craft" might be made by a multinational. The label isn’t the whole story.

The Future of Craft Beer

The craft beer boom peaked around 2019. Since then, growth has slowed. Over 2,100 U.S. craft breweries closed between 2020 and 2023. Competition is fierce. Big beer has learned to mimic craft styles. Consumers are tired of being misled.

The Brewers Association is quietly considering changes. One idea? Adding a "local economic impact" metric. Another? Requiring ownership disclosure on labels. Neither has been adopted yet.

For now, the definition remains unchanged. But the conversation is shifting. More drinkers are asking: "Who made this?" and "Where did it come from?" - not just "Does it taste good?"

Maybe the real craft beer isn’t defined by barrels or ownership percentages. Maybe it’s defined by intention - by the people who pour their passion into every batch, no matter how big or small the brewery.

Is craft beer always better than regular beer?

No. Craft beer isn’t automatically better. A 2022 blind taste test by Consumer Reports found no significant quality difference between many "craft-style" beers and mass-market lagers. Flavor depends on the brewer’s skill, ingredients, and process - not whether the brewery is labeled "craft." Some macro breweries make excellent, consistent beers. Some small breweries make flawed or boring ones.

Can a brewery be craft if it uses rice or corn?

Yes. Since 2014, the Brewers Association removed the ban on adjuncts like rice and corn. If they’re used to enhance flavor - not just cut cost - the beer still qualifies as craft. For example, some American lagers use rice to create a crisp, clean finish. That’s allowed. But if a brewery uses corn to make a cheap, watery beer and calls it "craft," it’s still technically eligible - even if it feels dishonest to drinkers.

Does craft beer have to be local?

No - not by the official definition. But many drinkers assume it is. A brewery in Oregon can be craft even if it ships beer nationwide. However, local ownership is what most consumers value. If you want to support your community, look for breweries headquartered near you - not just ones with "craft" on the label.

Why does ownership matter if the beer tastes good?

It doesn’t - if you only care about taste. But ownership affects the beer industry’s future. When big corporations buy craft breweries, they often shift focus from innovation to profit. Recipes get standardized. Experimental batches disappear. Independent brewers lose shelf space. For some, supporting truly independent breweries is about preserving diversity, not just flavor.

Are all craft beers expensive?

Not necessarily. While some limited releases or barrel-aged stouts can cost $20 a bottle, many craft breweries offer solid, flavorful beers for $8-$12 a six-pack. In fact, some craft lagers and pale ales cost less than premium macro brands. Price depends on ingredients, scale, and distribution - not the "craft" label itself.

If you want to know what craft beer really is, stop looking at the label. Start looking at the people behind it.